by Samuel Dunn Houston, San Antonio

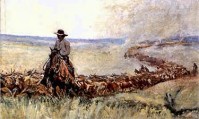

IN 1879 I WENT THROUGH SOUTHERN TEXAS with a big herd of cattle to the Northern market, Ogallala, Nebraska. This herd belonged to Head & Bishop.

We reached Ogallala Aug. 10, 1879, and there we met R.G. Head, who gave the boss, John Sanders, orders to cross the South Platte the next morning and proceed to the North Platte. He said he would see us over there and would tell us where to take the herd.

On August 11 we crossed the South Platte and went over on North River about ten miles and camped. Dick Head came over to camp for dinner and told our boss to take the herd up to Tusler’s Ranch on Pumpkin Creek and Mr. Tusler would be there to receive the cattle. He said it was about one hundred miles up the Platte.

After dinner we strung the herd out and drove them up there. We rushed them up because we were anxious to get back to Ogallala to see all of our old cowboy friends get in from the long drive from Texas.

We reached the Tusler Ranch on August 19 and on the 20th we counted the old herd over to the ranch boss and started back to Ogallala, making the return trip in four days.

The next morning as we were going through town, I met an old trail boss, and he wanted me to go with him to Red Cloud Agency, Dakota, with 4,000 big Texas steers that belonged to D.R. Fant. They were Indian contracted cattle, so I told the boss I was ready to make the trip. Tom Moore was the foreman’s name and he was a man that knew how to handle a big herd.

I went to camp with Tom that night and he got all the outfit together and on August 28 we took charge of the big herd. They were one of the old King herds, which had come in by way of Dodge City, Kansas, from the old coast country down in Southern Texas.

They wanted to walk, so we strung them out and headed for the old South Platte. When the lead cattle got to the bank of the river the boss said, “Now, Sam, don’t let them turn back on you, and we won’t have any trouble.” We landed on the other side all OK and went through the valley and on through the town.

Everybody in town was out to see the big King herd go through. I threw my hat back on my head and I felt as though the whole herd belonged to me.

When the lead cattle struck the foothills I looked back and could see the tail end coming in the river, and I told my partner, the right-hand pointer, that we were headed for the North Pole. We raised our hats and bid Ogallala good-bye.

When the lead cattle got to North River it was an hour and ten minutes before the tail end got to the top of the hills. My partner and I threw the range cattle out of the flats and we had it easy until the chuck wagon came over and struck camp for noon, then four of us boys went to camp.

We had a highball train from there on. We didn’t cross the North Platte until we got to Fort Laramie, Wyoming. The snow was melting in the mountains and the river was muddy and no bottom to the quicksand. I was looking every night for a stampede, but we were lucky.

The night we camped close to the Court House Rock, they made a jump off the bed ground, but that didn’t count. I think they got wind of the old Negro cook. This herd had come from the old King Ranch, away down in Texas with a Mexican cook. I told the boss that the next morning and he said he was almost sure that was the cause.

The North Platte River in places is more than a mile wide and it seemed to me when we reached the place we were to cross, it was two miles wide. The range cattle on the other side looked like little calves standing along the bank.

When we reached Fort Laramie we made ready to cross. I pulled my saddle off and then my clothes. Tom came up and said, “Sam, you are doing the right thing.”

I told him I had crossed that river before and that I had a good old friend who once started to cross that river and he was lost in the quicksand. His name was Theodore Luce of Lockhart, Texas. He was lost just above the old Seven Crook Ranch above Ogallala. Tom told all the boys to pull off their saddles before going across. When everything was ready we strung the herd back on the hill and headed for the crossing. Men and steers were up and under all the way across.

We landed over all safe and sound, got the sand out of our hair, counted the boys to see if they were all there and pulled out to the foothills to strike camp.

About ten o’clock that night the first guards came in to wake my partner and I to stand second guard. I got up, pulled on my boots, untied my horse and then the herd broke. The two first guards had to ride until Tom and the other men got there. Three of us caught the leaders and threw them back to the tail end, then ran them in a mill, until they broke again. We kept that up until three o’clock in the morning, when we got them quieted.

We held them there until daylight, then strung them toward the wagon and counted them. We were out fifty-five head, but we had the missing ones back by eight o’clock. We were two miles from the grub wagon when the run was over. The first guards said that a big black wolf got up too close to the herd and that was the cause of the trouble.

Our next water was the Nebraska River, which was thirty miles across the Laramie Plains. We passed over that in fine shape. From there our next water was White River. The drive through that country was bad, because the trail was so crooked with such deep canyons. We reached White River, crossed over and camped.

About the time we turned the mules loose, up rode about thirty bucks and squaws, all ready for supper. They stood around till supper was ready and the old Negro cook began to get crazy and they couldn’t stay any longer. They got on their horses and left.

An Indian won’t stay where there is a crazy person. They say he is the devil.

The next morning the horse rustler was short ten head of horses. He hunted them until time to move camp and never found them, so Tom told me that I could stay there and look them up, and he would take the herd eight or ten miles up the trail and wait for me. I roped out my best horse, got my Winchester and six-shooter and started out looking for the horses. I rode that country out and out, but could not find them, so I just decided the Indians drove them off during the night to get a reward or a beef.

I thought I would go down to the mouth of White River, on the Missouri River in the bottom where the Indians were camped. When I got down in the bottom I saw horse signs, so I was sure from the tracks they were our horses. I rode and rode until I found them. There was no one around them, so I started back with the bunch.

When I had covered three or four miles, I looked back and saw a big dust on the hill out of White River. Then I rode for my life, because I knew it was a bunch of Indians and they were after me. I could see the herd ahead of me, and never let up. I beat them to camp about a half mile.

When they rode up and pointed to the horses, one Indian said, “Them my horses. This man steal ‘em! Him no good!” We had an old squaw humper along with us, and he got them down to a talk and Tom told them he would give them a beef. Tom went with them out to the herd and cut out a big beef and they ran it off a short distance and killed it, cut it up, packed it on their ponies and went back toward White River.

If those Indians had overtaken me I am sure my bones would be bleaching in that country today. The Indians were almost on the warpath at that time and we were lucky in that we did not have any more trouble with them.

A week longer put us at the Agency. Tom went ahead of the herd and reported to the agent. We camped about four miles this side that night and the next morning we strung the old herd off the bed ground and went into the pens at Red Cloud Agency, Dakota. There I saw more Indians than I ever expected to see. The agent said there were about 10,000 on the ground.

It took us all day to weigh the herd out, ten steers on the scales at one time. We weighed them and let them out one side and the agent would call the Indians by name and each family would fall in behind his beef and off to the flats they would go.

After we got the herd all weighed out the agent told us to camp there close and he would show us around. He said the Indians were going to kill a fat dog that night and after they had feasted they would lay the carcass on the ground and have a war dance.

All the boys wanted to stay and see them dance. A few of the bucks rode through the crowd several times with their paint on. In a little while a buck came up with a table on his head and set it down in the crowd and then came another with big butcher knives in his hand and a third came with a big fat dog on his shoulder, all cleaned like a hog.

He placed it on the table, then every Indian on the ground made some kind of a pow-wow that could be heard for miles, after which the old chief made a speech and the feast began. Every Indian on the ground had a bite of that dog.

They wanted us to go up and have some, but we were not hungry, so we stood back and looked on. “Heap good,” said the chief, “heap fat.” About ten o’clock they had finished eating and two squaws took the carcass off the table and put it on the ground and the dance began. Every Indian was painted in some bright color. That was a wonderful dance.

The next morning we started back over our old trail to Ogallala. It was about October 16 and some cooler and all of the boys were delighted to head south. Seven days’ drive with the outfit brought us back to the Niobrara River and we struck camp at the Dillon Ranch.

The Dillon Ranch worked a number of half-breed Indians. I was talking with one about going back to Ogallala, as I was very anxious to get on the trail road and go down in Texas to see my best girl.

He told me he could tell me a route that could cut off 200 or 300 miles going to Ogallala. So I wrote it all down. He told me to go over the old Indian trail across the Laramie Plains, saying his father had often told him how to go and the trail was wide and plain and it was only 175 or 200 miles.

Right there I made up my mind that I would go that way and all alone. There were only two watering places and they were about forty miles apart. The first lake was sixty-five or seventy miles.

I had the best horse that ever crossed the Platte River and if I could cut off that much I would be in Texas by the time the outfit reached Ogallala.

I asked Tom to pay me off, saying that I was going back to Texas over the old Indian trail across the Laramie Plains. I knew if an Indian crossed that country I could also.

He said, “You are an old fool. You can’t make that trip, not knowing where the fresh water is, you will starve to death.” I told him that I could risk it anyway, and I knew I could make it.

Next morning I was in my saddle by daylight, bade the boys good-bye and told them if they heard of a dead man or horse on the old Indian trail, across the plains, for some of them the next year to come and pick me up, but I was sure I could make the trip across.

The first day’s ride I was sure I had covered sixty-five or seventy miles. I was getting very thirsty that evening, so I began to look on both sides of the trail for the fresh water lake, but was disappointed. I was not worried. Just as the sun went down I went into a deep basin just off the trail where there was a very large alkali lake.

I had a pair of blankets, my slicker and saddle blankets, so I made my bed down and went to bed. I was tired and old Red Bird (my horse) was also jaded. I lay awake for some time thinking and wondering if I was on the wrong trail.

The next morning I got up, after a good rest, ate the rest of my lunch, and pulled down the trail looking on both sides of the trail for the fresh water lake, but failed to find it. I then decided that the half-breed either lied or had put me “up a tree.”

Anyway, I would not turn back. I had plenty of money, but that was no good out there. I could see big alkali lakes everywhere, but I knew there would be a dead cowboy out there if I should take a drink of that kind of water.

I rode until noon, but found nothing. The country was full of deer, antelope, elk and lobo wolves, but they were too far off to take a shot at. When I struck camp for noon I took the saddle off my horse and lay down for a rest. Got up about one-thirty and hit the trail.

That was my second days’ ride and my tongue was very badly swelled. I could not spit anymore, so I began to use my brain and a little judgment and look out for “old Sam” and that horse.

About the middle of the afternoon I looked off to my left and saw a large lobo wolf about one hundred yards away and he seemed to be going my route. I would look in his direction quite often. He was going my gait and seemed to have me spotted. I took a shot at him every little while, but I kept on going and so did he. I rode on until sundown and looked out for my wolf, but did not see him.

The trail turned to the right and went down into a deep alkali basin. I rode down into it and decided that I would pull into camp for the night, as I was very much worn out. I went down to the edge of the lake, pulled off my saddle and made my bed down on my stake rope so I would not lose my horse. The moon was just coming up over the hill.

I threw a load in my gun and placed it by my side, with my head on my saddle, and dropped off to sleep. About nine o’clock the old wolf’s howls woke me up. I looked up and saw him sitting about twenty feet from my head just between me and the moon.

I turned over right easy, slipped my gun over the cantle of my saddle and let him have one ball. He never kicked. I grabbed my rope, went to him, cut him open and used my hands for a cup and drank his old blood.

It helped me in a way, but did not satisfy as water would. I went down to the lake and washed up, went back to bed and thought I would get a good sleep and rest that night, but found later I had no rest coming.

I was nearly asleep when something awakened me. I raised up and grabbed my gun, and saw that it was a herd of elk, so I took a shot or two at them. As soon as I shot they stampeded and ran off, but kept coming back. About twelve o’clock I got up, put my saddle on my horse and rode until daylight. I was so tired, I thought I would lay down and sleep awhile.

Riding that night I must have passed the second water lake. After sleeping a little while I got up and broke camp and rode until twelve o’clock, when I stopped for noon that day.

That being my third day out, I thought I would walk around, and the first thing I saw was an old dead horse’s bones. I wondered what a dead horse’s bones were doing away out there, so I began to look around some more and what should I see but the bones of a man.

I was sure then that some man had undertaken to cross the plains and had perished, so I told old Red Bird (my horse) that we had better go down the trail and we pulled out.

That evening about four o’clock, as I was walking and leading my horse, I saw a very high sand hill right on the edge of the old trail. I walked on to the top of the sand hill and there I could see cottonwood trees just ahead of me.

I sat down under my horse about a half an hour. I could see cattle everywhere in the valley, and I saw a bunch of horses about a mile from me. I looked down toward the trees about four miles and saw a man headed for the bunch of horses.

I didn’t know whether he was an Indian or not. He was in a gallop and as he came nearer to the horses I pulled my gun and shot one time. He stopped a bit and started off again. Then I made two shots and he stopped again a few minutes.

By that time he had begun to round up the horses, so I shot three times. He quit his horses and came to me in a run. When he got up within thirty of forty feet of me he spoke to me and called me by my name and said, “Sam you are the biggest fool I ever saw.”

I couldn’t say a word for my mouth was so full of tongue, but I knew him. He shook hands and told me to get up behind him and we would go to camp. He took his rope and tied it around my waist to keep me from falling off, for I was very weak.

Then he struck a gallop and we were at camp in a very few minutes. He tied his horse and said, “Now, Sam, we will go down to the spring and get a drink of water.”

Just under the hill about twenty steps was the finest sight I ever saw in my life. He took down his old tin cup and said, “Now, Sam, I am going to be the doctor.”

I was trying all the time to get in the spring, but was so weak he could hold me back with one hand. He would dip up just a teaspoonful of the water in the cup and say, “Throw your head back,” and he poured it on my tongue. After a while he increased it until I got my fill and my tongue went down. When I got enough water then I was hungry. I could have eaten a piece of that fat dog if I’d had it.

My friend’s name was Jack Woods, an old cowboy that worked on the Bosler Ranch. Jack and I had been up the trail from Ogallala to the Dakotas many times before that.

Jack said, “Now, Sam, we will go up to the house and get something to eat. I killed a fat heifer calf yesterday and have plenty of bread cooked, so you come in and lay down and I will start a fire quickly and cook some steak and we will eat some supper.”

Before he could get it cooked, I could stand it no longer, so I slipped out, went around behind the house where he had the calf hanging, took out my pocket knife and went to work eating the raw meat, trying to satisfy my appetite.

After fifteen or twenty minutes Jack came around hunting me and said, “Sam, I always thought you were crazy, now I know it. Come on to supper.” I went in the house and ate a hearty supper.

After finishing supper, I never was so sleepy in my life. Jack said, “Sam, lay down on my bed and go to sleep and I will go out and get your horse and treat him to water and oats.” He got on his horse and struck a gallop for the sand hills, where my poor old horse was standing starving to death.

Next morning Jack told me that a man by the name of Lumm once undertook to cross those plains from the Niobrara River to the head of the Little Blue over that same Indian trail. Jack said, “He and his horse’s bones are laying out on the plains now. Perhaps you saw them as you came along.”

I told him I saw the bones of a man and the horse, but didn’t remember how far back it was. It seemed about twenty-five miles.

I remained there five days and every morning while I was there, Jack and I would get on our horses and go out in the valley and round up the horses he was taking care of, rope out the worst outlaw horse he had in the bunch and take the kink out of his back. The five days I was there I rode four and five horses every day.

On October 29 I saddled my horse and told Jack I was going to Texas. He gave me a little lunch, and I bid him good-bye and headed for the North Platte. I reached Bosler’s Ranch at 12:20 p.m., had dinner, gave the boss a note from Jack Woods, fed my horse, rested one hour, saddled up, bade the boys good-bye and headed for Ogallala on the South Platte, forty miles below.

I reached Ogallala that night at 9:30, put my horse in the livery stable, went up to the Leach Hotel and there I met Mr. Dillon, the owner of the Niobrara Ranch, sold my horse to him for eighty dollars, purchased a new suit, got a shave and haircut, bought my ticket to Texas, and left that night at 11:30 for Kansas City.

On November 6 I landed in Austin, Texas, thirty miles from my home, and took the stage the next morning for Lockhart. That was where my best girl lived, and when I got there I was happy.

This was the end of a perfect trip from Nebraska on the South Platte to Red Cloud Agency, North Dakota.